I’ve always been a vocal critic of the ‘never eat before bed’ rule.

What whole ‘never eat after 7pm’ thing? What’s the reasoning behind it? Sure, metabolic rate slows during the night, but that doesn’t mean your bedtime snack is going to ‘stick to your thighs’ (what people used to say…in the 90s).

I’ve always felt that going to bed hungry can not only disrupt sleep, it can also be emotionally defeating. If you can’t eat when you’re hungry, if you can’t satisfy the very basic need to feed yourself, what does that say about your relationship with food?

Recently though, I’ve heard a lot about chrononutrition, which is essentially, eating according to your circadian rhythm. Daytime good. Nighttime bad. All of that.

I decided to take a look at the research around chrononutrition. There are a ton of new studies that explore circadian rhythm and eating, and I eagerly dove in.

I had a few questions, including:

Does the time of day at which we eat, really have an impact on our weight?

How about those European countries where the evening meal isn’t eaten until 10pm, yet they’re on average, thinner than North Americans?

How does eating at night impact, if it all, our blood sugars, insulin, and nutrient metabolism?

Eat your Wheaties, because we’re about to get into some serious research.

What is circadian rhythm?

The circadian rhythm is your body’s master clock. It’s run by the suprachiasmatic nucleus, which is a region in your brain’s hypothalamus. Pretty much every cell in your body has its own ‘clock’ that’s governed by the ‘master pacemaker’ in the brain.

The circadian rhythm follows a 24-hour clock, regulating physical, mental, and behavioural factors like the sleep-wake cycle, digestive system, and hormones. It’s impacted by light and darkness, but also by glucocorticoids, temperature, feeding, metabolic state, and sleep history.

For example, when the cells in the brain detect that daylight is waning, they send signals to the pineal gland – another centre in the brain – to secrete melatonin.

Melatonin is a hormone that promotes sleep. The time at which your brain begins to secrete melatonin in response to dim light is called the Dim Light Melatonin Onset, or DLMO.

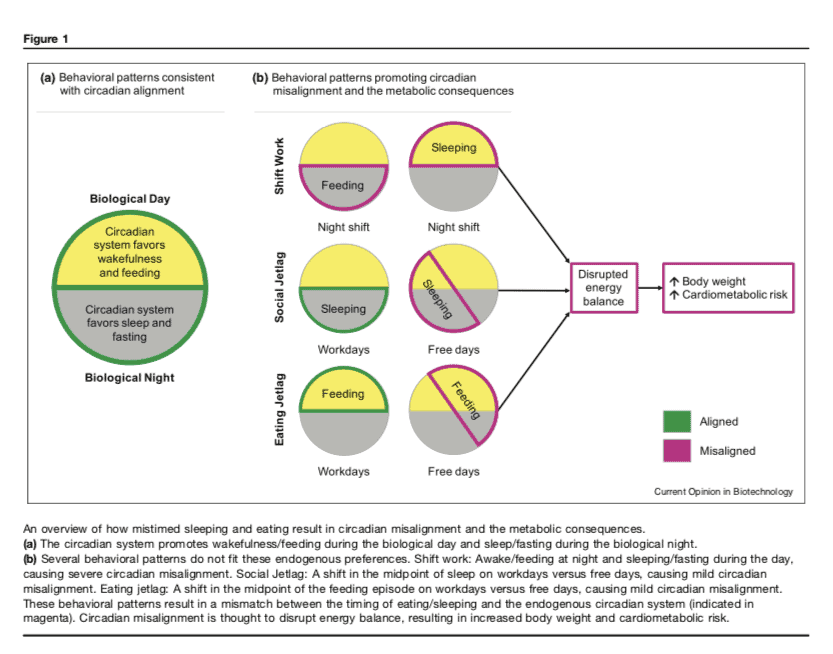

Shiftwork, sleep disorders, and jet lag can disrupt your circadian rhythm. This is called ‘misalignment,’ and is thought to be linked to obesity, heart disease, and diabetes.

Here is a fantastic graphic from a recent study in Current Opinion in Biotechnology, showing how circadian rhythm can be disrupted not only by shiftwork, but by everyday routines – like, for example, going out late and then sleeping in on the weekend (also termed ‘social jet lag’):

Sleep, melatonin, and eating before bed.

Recent studies seem to demonstrate some pretty clear-cut consequences of eating late at night.

A 2015 study in Current Biology found that participants whose sleep was shortened and who received a meal during the ‘biological night,’ had reduced insulin sensitivity, and an increased insulin response to carbohydrate. This 2018 study in Industrial Health corroborates these findings.

In people who do shiftwork, even when calories were equal to their days off, this 2020 review of studies in Frontiers in Nutrition found that there appears to be metabolic dysregulation as a result of eating over a 24-hour period.

Research suggests that levels of non-esterified fatty acids (NEFA) – fats floating around in the blood after a meal, high levels of which are associated with the development of heart disease – are higher after evening meals than morning meals.

We also know that there’s a ‘diurnal variation in insulin sensitivity’ in healthy people, meaning that insulin sensitivity (which you want to be high) is naturally lower in the evening.

An amazing 2017 review of studies in Obesity Reviews ties together circadian misalignment by short sleep and eating in the middle of the night with obesity, poor metabolic health, and weight gain.

And these results don’t seem to be solely the result of overeating, but also impaired metabolism due to this misalignment: ‘a calorie is no longer a calorie because metabolic outcomes are dependent on the circadian timing of food intake.’

So how does this all relate to us in real life?

While this extremely thorough and informative review of studies published in 2020 in the Journal of Neurochemistry found that people whose largest meal is in the evening may be heavier and have higher lipids and blood sugar after eating, this doesn’t mean that you need to skip dinner or go to bed hungry.

In my highly-popular recent review of a local ‘weight loss expert,’ I wrote about them telling their followers to not eat after the sun goes down, because the release of melatonin when darkness falls, signals to the body that we should be sleeping, not eating. That our body doesn’t use food that we eat after dark.

They also recommend not eating before bed under any circumstances. Preposterous.

In fact, someone who tells you not to eat when you’re hungry, is likely selling you a diet that promotes starvation and fosters guilt and shame around eating – nothing I would ever recommend.

Nothing bad is going to happen if you eat a balanced dinner earlier in the evening, or have a small, protein-rich snack to quell hunger pangs before you go to bed. Your body knows what to do with the food you consume in the dark, trust me.

‘It’s about total energy distribution throughout the whole day,’ says Alan Flanagan MSc, PhD, founder of Alinea Nutrition, and author of this 2020 study that I reference throughout this post (because it’s so darn great.)

Says Flanagan, ‘in people with impaired glucose control, the evidence is overwhelmingly in favor of greater distribution of total daily energy earlier in the day…when over 35% of energy comes later in the day, that’s pretty consistently associated with increased BMI, body fat percentage, and cardiometabolic risk, in particular diabetes risk.’

The timing of melatonin release – your DLMO (which is individualized between people) seems to have a lot to do with how your body deals with food. That’s where the ‘expert’ was correct. But like any good charlatan, they take that kernel of truth and spin it into something else.

What’s your chronotype?

People naturally have different ‘chronotypes,’ meaning, their natural preference for sleep-wake routines.

You might like to go to bed early and wake up early (early chronotype), but your friend might be up half the night and wake up late (late chronotype).

Chronotype is determined by genetics, environment, and age. Kids tend to have an earlier chronotype, while teenagers have a later one.

Because people who get up later tend to eat the majority of their calories later in the evening, this could put them at risk for health issues.

Even if you’re a late chronotype, according to Flanagan, it’s recommended that the greater proportion of energy is consumed over the first couple of meals, rather than at your last one.

When I asked him why people in Europe seem to not suffer any health effects from eating later at night, he responded that this eating pattern isn’t present in all that many countries, and where it is, they aren’t eating huge meals in the evening.

He also said that in countries where late-night eating is popular, people are ‘not maintaining health over the long-term.’

They’re also eating breakfast, and they don’t tend to overeat during the day. That too.

All of this matters.

Circadian rhythm and time restricted eating.

Here’s the thing: time restricted eating, otherwise known as intermittent fasting, limits food consumption to a relatively short window in a 24-hour period – usually 8 hours.

When you have fewer eating occasions, like you do (or should) when you restrict your eating to 8 hours a day, you naturally take in fewer calories.

We know that this eating pattern has been associated with weight loss, increased insulin sensitivity, and lowered blood pressure. We suspect that these effects might have something to do with fasting, but we aren’t sure whether they’re due to the weight loss, or to meal timing and alignment with circadian rhythm.

It is thought that shiftworkers who restrict their eating to the active phase of the day (and not the ‘rest phase’ may avoid metabolic consequences of eating over a 24 hour period.

The bottom line is that while time restricted eating may help some people avoid overeating at night, whether it works directly with circadian rhythm to decrease disease risk is still unknown.

Does eating earlier in the day give us a ‘thermodynamic advantage’?

In other words, do we burn more of the calories we eat, when we eat them earlier in the day?

We suspect that circadian rhythm may have a link to diet-induced thermogenesis in that, we burn more calories at breakfast than we do at dinner.

But the research seems to show that even if we do burn more calories from our breakfast than our lunch, the difference is very slight.

So, this really isn’t something that you should be concentrating on.

The bottom line on chrononutrition is this:

There definitely is evidence to show that late-night eating – in particular of full meals – is associated with impaired metabolic function. If you’re eating the majority of your calories in the latter part of the day, you might want to rethink that.

Skipping dinner or going to bed hungry shouldn’t even be considered. ‘That’s ludicrous,’ says Flanagan.

Should you be sitting down to a huge meal at 10pm that’s 40% of your calories? Probably not.

But if you want a snack before bed, Flanagan and I are aligned with our recommendations: ‘evidence shows that protein doesn’t negatively affect glucose and lipid metabolism and tolerance in the evening.’

Meaning, a lower-fat and carb, higher protein snack is ideal.

When you eat does matter, but what you eat, and how much, also matter. Try to keep the same eating schedule as much as you can. Try not to eat large meals at night.

And please don’t listen to nutrition ‘experts’ who don’t know what they’re talking about.